What to do with Job’s Final “Friend,” Elihu

Elihu is a strange character, at least in the sense of how and where he appears in the book of Job. Why does he not appear with the other three “friends?” Does his argument differ from any of the first three who argue with progressive vociferousness against Job as he suffers in unexplained (to him) torment? Is Elihu adding something to the discussion that needs to be heard by Job—something preparatory? Is he simply used as a way of synthesizing the eight arguments we have heard from the other friends already?

What needs to be noted about the entire book of Job that seems to get precious little attention is that it is built, in large part, on a dirge pattern. Of course, the average Christian (if there is such a person) knows nothing of ancient literary patterns. And yet, whether one knows to call it a dirge pattern or a qinah (Hebrew for “lament”) pattern or a “dying-out” pattern makes no difference to the fact that it is easily identifiable by any attentive reader. The bulk of the book, however (a full twenty-eight of forty-two chapters!), is made up of the arguments of the first three friends and Job’s responses to them.

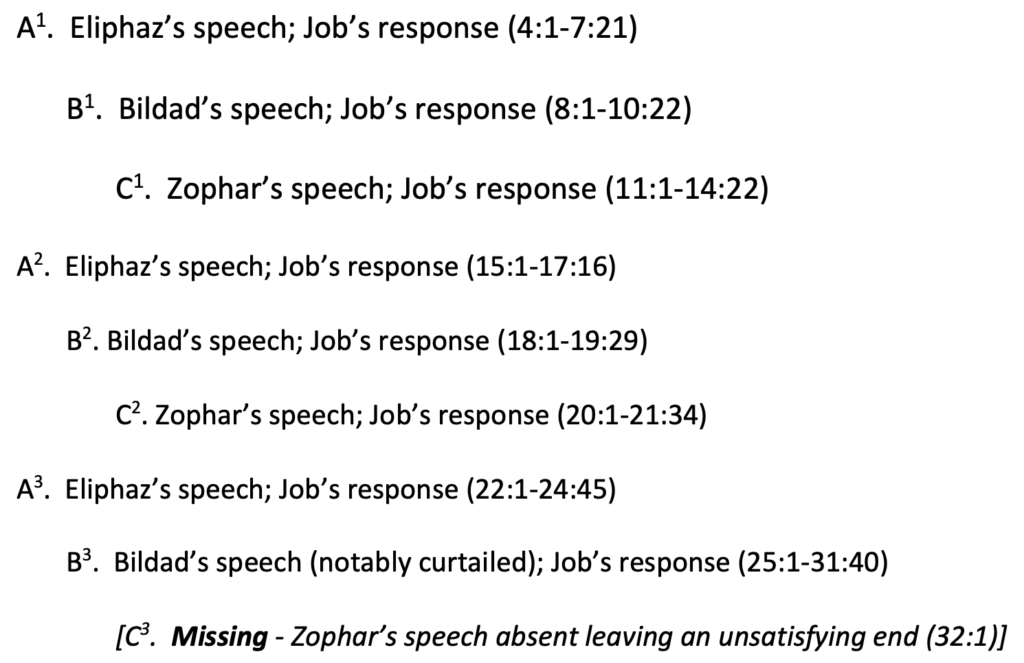

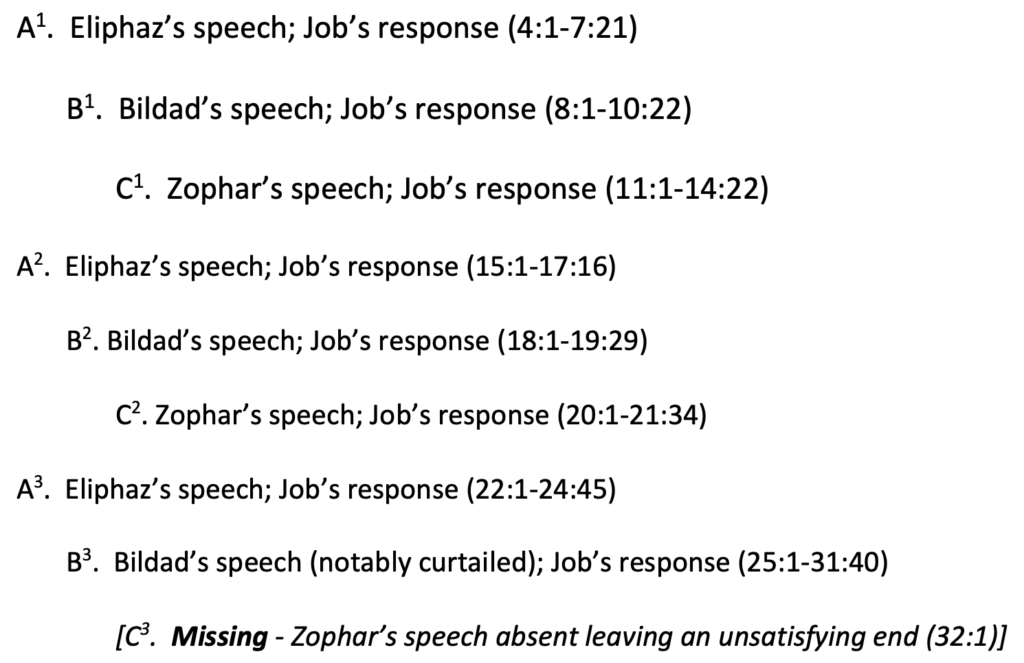

Even a cursory reading of the speeches of the first three friends shows immediately that they are arranged in an orderly, patterned manner. First, Eliphaz speaks, then Bildad, then Zophar. Each speech of the three receives its own rebuttal from Job. Then the pattern is repeated, again complete with individual rebuttals. Then the pattern is repeated again, complete with rebuttals, but with a twist the third time—a highly noticeable and ingenious twist. This final time, there is no speech from the third friend, Zophar. The second friend, Bildad, has a notably curtailed speech in Job 25 of just a mere 5 verses! No attentive reader could miss the massively abrupt modification. Even if one did not know to pay attention for such structural deviations, the fact that the pattern has been overtly displayed as “Eliphaz-Bildad-Zophar” would be unmistakable. When reaching the point of where Zophar’s final speech would be—should be—the reader’s mind should immediately be forced to ask the question, Why is there no final speech from Zophar?

The literary structure of this section of Job can be displayed like this:

All of this ultimately leaves the reader quite unfulfilled. What he had been taught to expect was a speech from Eliphaz (with Job’s response) followed by a speech from Bildad (with Job’s response) followed by a speech from Zophar (with Job’s response). The fact that the pattern ends abruptly is highly disconcerting. Where in the world is the third pig who built his house out of bricks? Where is the third bed that Goldilocks slept in? This literary device is completely unfinished. Either the author is a moron or crazy or there is something very important being said as much by form as by verbiage.

This dirge pattern is actually screaming to the reader that something has gone terribly wrong. According to David Dorsey, Lamentations is written in a dirge pattern.[i] Also, the ending of Mark’s Gospel (with only fear and speechlessness in 16:8) is the final piece of a dirge pattern. Both of these come at pivotal and desperate moments in Israel’s history—one is the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon and the other is the death and missing corpse of the long-awaited Messiah. The structures of both hold the clues for understanding what the author is striving to convey.

It should come as no shock that the author of Job is using a similar structure to describe such dire circumstances which have befallen righteous Job. In 32:1, the reader is told, “So these three men ceased to answer Job, because he was righteous in his own eyes.” They are not going to speak anymore?! Were these words the end, the hearer/reader would be left pondering that Job has only to languish in his unresolved thoughts and sufferings until he dies. No one has any good answers for him? How can this be the end?!

But there is yet hope. And this hope comes from a most unexpected avenue. This young man—Elihu—is someone of whom the reader has never heard. There was no inkling that a fifth member of the conversation might be allowed input. And yet, he inserts himself here, immediately following Job’s final rebuttal and just when all hopes of reaching out to Job or finding answers to his questions seem lost.

We must note this placement for more reasons than filling the blank in the dirge pattern. Job has been wishing for someone who could stand between him and God for some time now, an advocate who could plead with God on his behalf and be heard (9:32-34; 16:19-21; 19:25). Job believes he would only be utterly crushed and unable to plead his own case in God’s presence (9:14-20; 19:6-12). This advocate would be one who “might lay his hand upon us both” (9:33). He would be between them, speaking for Job so that Job might then be able to stand before God (19:26-27). This is the role of Elihu even on a simple literary structural level. His speech (3 speeches, actually, just like the other “friends”)[ii] comes in between Job’s final railing (26:1-31:40) and God’s two speeches to Job (38:1-41:34). Elihu is the one who stands between them, uniquely positioned literarily between Job and God. He sets about retraining Job to listen so that he will be ready to hear God.

In the end, Job does stand before God in his own body, neither crushed by tempest nor having his breath taken from him nor counted as God’s adversary, to be sure (cp. 9:17-18; 19:11). He is asked questions by God in two separate speeches, both times being told to “Dress for action like a man” and answer questions from God (38:3; 40:7). His answer is essentially, “I spoke rashly….Now that I see you I repent with all fervency” (cp. 42:3, 5-6). But his coming before Yahweh does not take place until after Elihu’s surprise—yet most timely—insertion.

Among the first things we learn about Elihu is that he “burned with anger at Job because he justified himself rather than God.” Burned with anger is a phrase used six times in Job[iii] and there are only two subjects of the phrase—God and Elihu. This despite the fact that Job seems angry through the better part of the book at both God and his friends, while his three friends increase substantially in their harsh feelings toward Job as the book continues. Elihu burns with anger at Job for justifying himself rather than God (32:2) but also toward the friends because they found no answer for Job (32:3, 5, 12).

Also deemed important for the reader to know is that Elihu is a young man, at least in comparison to this small crowd (32:4, 6). He is careful to speak last, only after the others have exhausted their arguments which have now proven to be hollow.

Though some propose that Elihu is only regurgitating arguments of the first three friends, Elihu makes clear that he is not going to answer Job with what was already offered (32:14).

The reader is told by Elihu that his answers will come from the Spirit that has given him wisdom to speak (32:8) and that now constrains (oppresses) him to speak forth (32:18). It is the Spirit of God that has made Elihu, he asserts (33:4). Elihu declares that he is “perfect in knowledge” (36:4), which is something he states clearly only about himself and God (cf. 37:16). He also says his knowledge comes from afar (36:3).

Elihu tells Job he need not be afraid when Elihu speaks the truth to him because he is a man, made of clay, just as Job (33:6). In other words, he is a human and his presence will not frighten Job even though Elihu will speak the wisdom from God to him.

Before getting to his first argument, Elihu brings up, like Job, the idea of a mediator who can speak to/for one who is going down to “the pit” (33:23). This one would surely die except for the mediator—“one in a thousand”—who offers a “ransom” for him (33:24; used only twice in Job, both by Elihu, cf. 36:18). After the ransom, however, the man is completely renewed and his flesh restored like a young man, healthy and whole (33:25). The renewal allows the man (foreshadowing Job’s own renewal) to stand before others proclaiming the forgiveness of God (33:27-28).

As for Elihu’s speeches, they are actually quite a far cry from those of the three friends, for whom the equation of “suffering = iniquity” is an easy one. Elihu spends time introducing himself, and expressing why he feels the need to speak in chapters 32-33. He wishes to offer correction to Job who has now contended several times that God is in the wrong for bringing suffering on him this way and that God refuses to speak to him about why. Elihu is going to offer the perspective that God speaks to men often and in many ways—dreams, warnings, pain, strife in the bones, hatred of food, deterioration of body, closeness of death, angels, mediators (33:14-23). God does all of this to stave off a person’s pride and reestablish his relationship with his Maker (33:17, 26, 30). Remember, the careful reader was forced to consider something might be going on in Job’s heart that needs correction since the strange statement of 2:10—“In all this Job did not sin with his lips” (cp. 1:22).

Elihu’s first argument is in chapter 34 and is addressed directly toward the first three friends (Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar; cf. 34:2, 10, 34). In 34:4-9, 35-37, we have two amalgamated quotes of the three friends who continued to charge Job with wrongdoing and refused to listen to his protests. Elihu repeats their words back to them, including their characterizations of Job’s words. Between these quotes, Elihu’s argument is that God has put the governors of people in place as he has chosen. He removes those who no longer have a heart for him and there is no evidence that Job is not a righteous judge. God knows what he is doing and will leave a person in place who will come to him at the proper time, and it is not a “wise man’s” place to say when that time should be ended. God is not obligated to punish or rebuke according to these “wise men’s” ways (34:33). As Leithart has pointed out, Elihu desires to justify Job (33:32).[iv] Therefore, their arguments against Job are moot on the basis that (1) they have no evidence to charge Job with wrongdoing since he is an impartial judge (34:17-19) and (2) God knows exactly what he is doing in Job to bring him inwardly to the proper position before God.

In his second argument, Elihu addresses Job in what can be encapsulated with idea that God will not be forced to give account for his actions to any person. He is God, for goodness sake, and demanding he play the defendant in court is both unacceptable and ridiculous (see esp. 35:12-14).

His third speech is one which emphasizes how far above our understandings are God’s ways. Elihu succinctly presents this argument in 36:22-23: “Behold, God is exalted in power; who is a teacher like him? Who has prescribed for him his way, or who can say, ‘You have done wrong’?” Thus, God’s dealings with Job, though they are beyond Job’s and his friends’ understanding, can be trusted as appropriate and just for Job’s best outcome. Elihu cautions Job to “let not the greatness of the ransom [atonement] turn you aside” (36:18). In other words, Elihu suggests to Job that this is a way of dealing with Job’s sin—something in his heart that never left his lips (2:10), quite likely—and whatever the cost should be considered worth it by Job. In fact, God has many reasons for allowing his great storms to come—such as to correct people, and/or to water the land, and/or to show his love (37:13). Job is questioned by Elihu if he can explain the natural wonders that God works (37:14-18), the very line of questioning God will immediately take up in the next chapter (38:4ff). As Elihu ends, he contends God has a reason for all of his actions and many of those are indiscernible by men. His power is too great next to ours for us to demand his accounting.

Hence, Elihu (“My God, Himself”) is a young man of greater wisdom than all of the old sages. He shows up just when all hope seems lost—when the dirge pattern threatens to be the final, unsatisfying end. He is “perfect in knowledge” as is God and speaks of himself as a “mediator” who brings with him a “ransom” for the one who is about to descend to the “pit.” He speaks wisdom that prepares the sufferer to be in God’s presence eventually leading to full restoration.

Who is Elihu? Why is he here? Does he belong in the story? As with many of our questions about Scripture, the answer is found in Luke 24:27.[v]

What to do with Job’s Final “Friend,” Elihu

Elihu is a strange character, at least in the sense of how and where he appears in the book of Job. Why does he not appear with the other three “friends?” Does his argument differ from any of the first three who argue with progressive vociferousness against Job as he suffers in unexplained (to him) torment? Is Elihu adding something to the discussion that needs to be heard by Job—something preparatory? Is he simply used as a way of synthesizing the eight arguments we have heard from the other friends already?

What needs to be noted about the entire book of Job that seems to get precious little attention is that it is built, in large part, on a dirge pattern. Of course, the average Christian (if there is such a person) knows nothing of ancient literary patterns. And yet, whether one knows to call it a dirge pattern or a qinah (Hebrew for “lament”) pattern or a “dying-out” pattern makes no difference to the fact that it is easily identifiable by any attentive reader. The bulk of the book, however (a full twenty-eight of forty-two chapters!), is made up of the arguments of the first three friends and Job’s responses to them.

Even a cursory reading of the speeches of the first three friends shows immediately that they are arranged in an orderly, patterned manner. First, Eliphaz speaks, then Bildad, then Zophar. Each speech of the three receives its own rebuttal from Job. Then the pattern is repeated, again complete with individual rebuttals. Then the pattern is repeated again, complete with rebuttals, but with a twist the third time—a highly noticeable and ingenious twist. This final time, there is no speech from the third friend, Zophar. The second friend, Bildad, has a notably curtailed speech in Job 25 of just a mere 5 verses! No attentive reader could miss the massively abrupt modification. Even if one did not know to pay attention for such structural deviations, the fact that the pattern has been overtly displayed as “Eliphaz-Bildad-Zophar” would be unmistakable. When reaching the point of where Zophar’s final speech would be—should be—the reader’s mind should immediately be forced to ask the question, Why is there no final speech from Zophar?

The literary structure of this section of Job can be displayed like this:

All of this ultimately leaves the reader quite unfulfilled. What he had been taught to expect was a speech from Eliphaz (with Job’s response) followed by a speech from Bildad (with Job’s response) followed by a speech from Zophar (with Job’s response). The fact that the pattern ends abruptly is highly disconcerting. Where in the world is the third pig who built his house out of bricks? Where is the third bed that Goldilocks slept in? This literary device is completely unfinished. Either the author is a moron or crazy or there is something very important being said as much by form as by verbiage.

This dirge pattern is actually screaming to the reader that something has gone terribly wrong. According to David Dorsey, Lamentations is written in a dirge pattern.[i] Also, the ending of Mark’s Gospel (with only fear and speechlessness in 16:8) is the final piece of a dirge pattern. Both of these come at pivotal and desperate moments in Israel’s history—one is the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon and the other is the death and missing corpse of the long-awaited Messiah. The structures of both hold the clues for understanding what the author is striving to convey.

It should come as no shock that the author of Job is using a similar structure to describe such dire circumstances which have befallen righteous Job. In 32:1, the reader is told, “So these three men ceased to answer Job, because he was righteous in his own eyes.” They are not going to speak anymore?! Were these words the end, the hearer/reader would be left pondering that Job has only to languish in his unresolved thoughts and sufferings until he dies. No one has any good answers for him? How can this be the end?!

But there is yet hope. And this hope comes from a most unexpected avenue. This young man—Elihu—is someone of whom the reader has never heard. There was no inkling that a fifth member of the conversation might be allowed input. And yet, he inserts himself here, immediately following Job’s final rebuttal and just when all hopes of reaching out to Job or finding answers to his questions seem lost.

We must note this placement for more reasons than filling the blank in the dirge pattern. Job has been wishing for someone who could stand between him and God for some time now, an advocate who could plead with God on his behalf and be heard (9:32-34; 16:19-21; 19:25). Job believes he would only be utterly crushed and unable to plead his own case in God’s presence (9:14-20; 19:6-12). This advocate would be one who “might lay his hand upon us both” (9:33). He would be between them, speaking for Job so that Job might then be able to stand before God (19:26-27). This is the role of Elihu even on a simple literary structural level. His speech (3 speeches, actually, just like the other “friends”)[ii] comes in between Job’s final railing (26:1-31:40) and God’s two speeches to Job (38:1-41:34). Elihu is the one who stands between them, uniquely positioned literarily between Job and God. He sets about retraining Job to listen so that he will be ready to hear God.

In the end, Job does stand before God in his own body, neither crushed by tempest nor having his breath taken from him nor counted as God’s adversary, to be sure (cp. 9:17-18; 19:11). He is asked questions by God in two separate speeches, both times being told to “Dress for action like a man” and answer questions from God (38:3; 40:7). His answer is essentially, “I spoke rashly….Now that I see you I repent with all fervency” (cp. 42:3, 5-6). But his coming before Yahweh does not take place until after Elihu’s surprise—yet most timely—insertion.

Among the first things we learn about Elihu is that he “burned with anger at Job because he justified himself rather than God.” Burned with anger is a phrase used six times in Job[iii] and there are only two subjects of the phrase—God and Elihu. This despite the fact that Job seems angry through the better part of the book at both God and his friends, while his three friends increase substantially in their harsh feelings toward Job as the book continues. Elihu burns with anger at Job for justifying himself rather than God (32:2) but also toward the friends because they found no answer for Job (32:3, 5, 12).

Also deemed important for the reader to know is that Elihu is a young man, at least in comparison to this small crowd (32:4, 6). He is careful to speak last, only after the others have exhausted their arguments which have now proven to be hollow.

Though some propose that Elihu is only regurgitating arguments of the first three friends, Elihu makes clear that he is not going to answer Job with what was already offered (32:14).

The reader is told by Elihu that his answers will come from the Spirit that has given him wisdom to speak (32:8) and that now constrains (oppresses) him to speak forth (32:18). It is the Spirit of God that has made Elihu, he asserts (33:4). Elihu declares that he is “perfect in knowledge” (36:4), which is something he states clearly only about himself and God (cf. 37:16). He also says his knowledge comes from afar (36:3).

Elihu tells Job he need not be afraid when Elihu speaks the truth to him because he is a man, made of clay, just as Job (33:6). In other words, he is a human and his presence will not frighten Job even though Elihu will speak the wisdom from God to him.

Before getting to his first argument, Elihu brings up, like Job, the idea of a mediator who can speak to/for one who is going down to “the pit” (33:23). This one would surely die except for the mediator—“one in a thousand”—who offers a “ransom” for him (33:24; used only twice in Job, both by Elihu, cf. 36:18). After the ransom, however, the man is completely renewed and his flesh restored like a young man, healthy and whole (33:25). The renewal allows the man (foreshadowing Job’s own renewal) to stand before others proclaiming the forgiveness of God (33:27-28).

As for Elihu’s speeches, they are actually quite a far cry from those of the three friends, for whom the equation of “suffering = iniquity” is an easy one. Elihu spends time introducing himself, and expressing why he feels the need to speak in chapters 32-33. He wishes to offer correction to Job who has now contended several times that God is in the wrong for bringing suffering on him this way and that God refuses to speak to him about why. Elihu is going to offer the perspective that God speaks to men often and in many ways—dreams, warnings, pain, strife in the bones, hatred of food, deterioration of body, closeness of death, angels, mediators (33:14-23). God does all of this to stave off a person’s pride and reestablish his relationship with his Maker (33:17, 26, 30). Remember, the careful reader was forced to consider something might be going on in Job’s heart that needs correction since the strange statement of 2:10—“In all this Job did not sin with his lips” (cp. 1:22).

Elihu’s first argument is in chapter 34 and is addressed directly toward the first three friends (Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar; cf. 34:2, 10, 34). In 34:4-9, 35-37, we have two amalgamated quotes of the three friends who continued to charge Job with wrongdoing and refused to listen to his protests. Elihu repeats their words back to them, including their characterizations of Job’s words. Between these quotes, Elihu’s argument is that God has put the governors of people in place as he has chosen. He removes those who no longer have a heart for him and there is no evidence that Job is not a righteous judge. God knows what he is doing and will leave a person in place who will come to him at the proper time, and it is not a “wise man’s” place to say when that time should be ended. God is not obligated to punish or rebuke according to these “wise men’s” ways (34:33). As Leithart has pointed out, Elihu desires to justify Job (33:32).[iv] Therefore, their arguments against Job are moot on the basis that (1) they have no evidence to charge Job with wrongdoing since he is an impartial judge (34:17-19) and (2) God knows exactly what he is doing in Job to bring him inwardly to the proper position before God.

In his second argument, Elihu addresses Job in what can be encapsulated with idea that God will not be forced to give account for his actions to any person. He is God, for goodness sake, and demanding he play the defendant in court is both unacceptable and ridiculous (see esp. 35:12-14).

His third speech is one which emphasizes how far above our understandings are God’s ways. Elihu succinctly presents this argument in 36:22-23: “Behold, God is exalted in power; who is a teacher like him? Who has prescribed for him his way, or who can say, ‘You have done wrong’?” Thus, God’s dealings with Job, though they are beyond Job’s and his friends’ understanding, can be trusted as appropriate and just for Job’s best outcome. Elihu cautions Job to “let not the greatness of the ransom [atonement] turn you aside” (36:18). In other words, Elihu suggests to Job that this is a way of dealing with Job’s sin—something in his heart that never left his lips (2:10), quite likely—and whatever the cost should be considered worth it by Job. In fact, God has many reasons for allowing his great storms to come—such as to correct people, and/or to water the land, and/or to show his love (37:13). Job is questioned by Elihu if he can explain the natural wonders that God works (37:14-18), the very line of questioning God will immediately take up in the next chapter (38:4ff). As Elihu ends, he contends God has a reason for all of his actions and many of those are indiscernible by men. His power is too great next to ours for us to demand his accounting.

Hence, Elihu (“My God, Himself”) is a young man of greater wisdom than all of the old sages. He shows up just when all hope seems lost—when the dirge pattern threatens to be the final, unsatisfying end. He is “perfect in knowledge” as is God and speaks of himself as a “mediator” who brings with him a “ransom” for the one who is about to descend to the “pit.” He speaks wisdom that prepares the sufferer to be in God’s presence eventually leading to full restoration.

Who is Elihu? Why is he here? Does he belong in the story? As with many of our questions about Scripture, the answer is found in Luke 24:27.[v]