Could Absalom be a Christ-type?

If you know much about the Bible, you likely have an immediate aversion to even the possibility of answering this question in the affirmative. Absalom was third among David’s sons, while Amnon—his brother from another mother—was first (2 Sam. 3:2-3). As Absalom’s story begins, it seems as much the story of Amnon and Absalom’s sister, Tamar, as anything.

Amnon decided he loved Tamar (2 Sam. 13:4). But his love was based on lust alone and once he had raped his beautiful half-sister, he saw her as unworthy of any further attention, let alone any chance at seeking to make amends. Even though Tamar sought to make some good out the terrible circumstance—encouraging Amnon to seek David’s approval for marriage—Amnon is unmoved (2 Sam. 13:15-19). Instead, she is ushered from his presence to live as a stained woman in her brother, Absalom’s house (2 Sam. 13:20).

At this point, our story shifts to become the story of Absalom. What the reader had thought might become the recounting of a story of an earlier Tamar that moved in a similar direction is not so (see Gen. 38—sexual sin followed by Tamar’s rejection and sullied reputation, and yet leading to her ultimate vindication before all). Or perhaps it is. But these are pieces that must be sorted out as our considerations continue.

Absalom cautions Tamar not to be vengeful against her brother and not to let his evil actions affect her (2 Sam. 13:20). She even seems to take his advice. Absalom, however, does not. After two years of biding time, he finds opportunity in a festival of celebration. Absalom tells his servants to kill Amnon at his command (13:28). This leads to Absalom’s fleeing for his life to Geshur where he lives in a sort of exile for three years (13:38; northeast of the Sea of Galilee—the same direction as Babylon). David is eventually comforted over the loss of Amnon and his heart longs to see his son, Absalom, again (13:39), though he makes no move to bring Absalom back to Israel.

It is Joab who seeks Absalom’s return (2 Sam. 14:1ff). Perhaps the reader should not be surprised. After all, Joab is a man of vengeance. His heart was displayed clearly in his plan and action to defy the reconciliation of David, his king, with Abner, Saul’s former general. Joab killed Abner in cold blood for the death of his brother (2 Sam. 3:26-30). For Joab, justice can be accomplished in revenge-killing, and having an heir apparent in Israel who is a man of such action may even be something he considers a step in a positive direction. More likely, however, is the anti-Solomonic determination of Joab as he seeks to insert the next king of Israel, himself, and he clearly supports either Absalom or Adonijah over Solomon. This theory, and a timeline helping establish its validity, is set forth by Leithart and deserves full attention for better understanding of Joab’s motives which are far from altruistic.[i]

The lion’s share of 2 Samuel 14 is spent on the ruse perpetrated on David by Joab and the woman he has enlisted to tell a story to David in order to get him to allow Absalom’s return from Geshur (14:1-24). Though David sees through the deception, he nevertheless grants Absalom’s return. Yet the father-king makes no move to communicate with Absalom nor have him brought into his presence for two years following the return (14:28).

The reader then learns in a somewhat out-of-place seeming paragraph that Absalom is the most handsome man in Israel. Although we are told of David’s “handsome appearance” more than once (1 Sam. 16:12; 17:42), the length to which the writer goes to ensure the reader that Absalom is more handsome than anyone else in Israel is striking. It is most reminiscent of Saul’s description in 1 Samuel 9:2 of whom the reader was told “not a man among the people of Israel was more handsome than he.” (The reader remembers clearly how Saul’s story ended.) This similarity and others between Saul and Absalom are not missed by Leithart.[ii]

Not satisfied with only stressing Absalom’s comeliness, however, the writer continues with another phrase. He adds that the young prince has “no blemish.” Including here, three Hebrew terms of the four used for this phrase in the original language are found in only 10 verses in the OT, each time referring to either a priest who is allowed to minister in the tabernacle before God because he has “no blemish” on him, or of the only acceptable sacrifices—those having “no blemish” (Lev. 21:17, 18, 21, 23; 22:20, 21, 25; Deut. 15:21; 17:1; 2 Sam. 14:25). Should we be considering Absalom’s possible role in a sacrificial offering in the future?

Another notable part of Absalom’s appearance is his hair (1 Sam. 14:26) which he cuts once a year. The length and weight of it were almost shocking. And yet, the reader is reminded of another character in the Scripture whose hair was considered his finest asset and yet who was known to succumb to prideful and personal desires and to ultimately suffer defeat, imprisonment, and death. Just as Samson, the mighty judge of Israel, had hair that wound up being a critical link in how God’s enemies brought about his defeat (Judges 16:19), so now this prideful usurper of his father’s throne will be defeated in a most unexpected way when he is pierced in a tree after having his hair entangled in the branches (2 Sam. 18:9, 14).

Finally, the reader is told in the short paragraph in 1 Samuel 14 that Absalom had three sons and one daughter. Most interesting, however, is that although the sons are left unnamed, the daughter’s name is made clear: Tamar (v.27). Including Genesis 38, and Tamar who we just read was raped by her brother, Amnon, there is now a third Tamar. It seems most natural to assume she was named for her aunt whose honor her brother so viciously avenged.

The reader is given no descriptors of Absalom’s sons at all, but of the daughter, Tamar, he is told, “She was a beautiful woman” (1 Sam. 14:27). Is this included to suggest the figurative redemption of the Tamar whose reputation was only so recently besmirched? Of all the uses of the two words in Hebrew translated “beautiful” other than here, we find them in tandem only to describe Sarah (Gen. 12:11), Rachel (Gen. 29:17), Joseph (Gen. 39:6), David (1 Sam. 17:42), Esther (Esth. 2:7); and the seven “attractive” cows of Pharaoh’s dream (Gen. 41). Why is Absalom’s daughter so closely linked to several figures who are at the heart of God’s redemptive plan for all of history, three of them being beautiful brides representing God’s people, as a whole?

At this point in the story, the reader’s attention is turned once again to the reconciliation of Absalom and David (2 Sam. 14:28-33). The final note in this section is wonderfully positive, too, for the author closes with the words that when Absalom was allowed to enter the presence of his father, he “bowed himself on his face to the ground” and “the king kissed Absalom” (14:33). The relationship is restored. It would seem there would be nothing left for the reader to do except rejoice. But wait. Much more is to come.

Absalom’s return to Jerusalem extends for four years (2 Sam. 15:7). During these years, he has often sat at the gate of the city, as a judge or counselor would sit. He has made many passive remarks to those who came seeking justice about how their legal circumstances would be greatly enhanced if Absalom only had more authority in Israel (15:4). He would also take by the hand those who sought to pay homage to him as a prince in Israel and kiss them. In this way, he “stole the hearts of the men of Israel” (15:6). These are the underpinnings of a bid for his father’s power.

At just the right moment in his strategic plan, Absalom goes to Hebron under false pretenses in order to be proclaimed the new king of Israel (2 Sam. 15:7, 10). Hebron is the same place where his father, David, first ruled over Judah (2 Sam. 2:1-4), later transferring his seat of power to Jerusalem (2 Sam. 5:9). This order of things is now followed by the upstart son. Once again, the usurper mimics the chosen, yet always with his own desires at the forefront.

The rest of the chapter involves word reaching David and his leading of his loyal servants out of Jerusalem by way of the Kidron Valley and the Mount of Olives (2 Sam. 15:23,30). A future king in the line of David will find his reign assailed by “sons” who wish to take it for themselves, and he will also choose the Kidron Valley and an ascent of the Mount of Olives as a way of refuge in desperate times (John 18:1; Luke 22:39). The reader is also told that one of David’s former counselor’s has now turned traitor and counsels the usurper in his bid for power (2 Sam. 15:12; 16:23), though his counsel will come to nothing and he will hang himself when his plan is thwarted and defeat is obvious (2 Sam. 17:23). Again, the connections to the future Davidic King are unmistakable (Matt. 26:14-16; 27:5).

In 2 Samuel 16, the focus is placed on those helping David in his retreat and those rejoicing at his potential eviction. Ziba, a servant in Saul’s house and now working for Saul’s grandson, Mephibosheth, is quick to offer aid to David in his retreat from Jerusalem. Shimei, of Saul’s house, also comes out to David during his flight but shows only animosity for him, hurling stones (verbal and real) at the flight of anointed one (16:5-8, 13). By the end of the chapter, upon Ahithophel’s advice, the usurper has taken David’s concubines for himself, seeking to solidify his place as the new king in full control of Israel.

Hushai—one of David’s closest friends and advisors—has previously been instructed by David to stay in Jerusalem to deceive Absalom by opposing Ahithophel’s advice (15:32-37). In chapter 17, this subversive rivalry is brought to the fore with Hushai’s advice being accepted over Ahithophel’s, leading to the suicide of the latter by the end of the chapter. It is what occurs in chapter 18 that shifts our typological perspective in the greatest way, however.

To this point we have seen Absalom as a redeemer for his sister and judge for his rapist brother. We have seen him as a son longing to come home and return into his father’s presence. We have seen him become the one who seeks to gain his father’s power for himself, even at the price of expelling his father from his home and potentially killing him. In 2 Samuel 18, we read about a great battle waged between forces of the father and his rebellious son. The father is exceedingly clear that he wants no physical harm to come to his son whom he loves dearly, instructing his highest commanders in the hearing of all (18:5). It is only four verses later that we find the loved son of that father suspended in a tree (18:9), and in only five more verses he is pierced three times in the same tree by Joab, one of the very commanders who clearly heard the father’s instructions for mercy (18:14). No one plays the deceptive Satan-type in the story of David more clearly than Joab, in his manipulations and outright disobedience of the father-king’s strict orders.[iii] Ten men closest to Joab then finish the son off while he hangs in the tree and his body is thrown into a pit and covered with stones (18:17). The father’s reaction when he hears the terrible news can be considered only the most intense level of grief. He even wishes he might have died in the son’s place (18:33).

The final chapter in the Absalom saga is 2 Samuel 19, and it is here that we find the day of great victory over those who sought to take the father’s kingdom from him by force is also a day of desperate sorrow because it involved the death of his beloved son (19:2, 4). It is a victory for the forces of the father, and yet the cost of it has left his loyal army ashamed (19:3). Perhaps the greatest insult is that the king-father’s right-hand man who should have carried out his orders for mercy cannot understand the grief of the king over the harsh death of his son (19:6-7).

The king is eventually restored to his position and upon his return he grants forgiveness to Shimei, who reveled in his earlier ousting from power (19:22-23). David also hears the story of Saul’s would-be heir to the throne, Mephibosheth, again extending grace when discerning between the conflicting accounts of him and his servant, Ziba (19:26-28; cp. 16:3).

Barzillai, who lived on the outside of the promised land, is given great favor by the king upon his return because of the kindness he showed David during the retreat from Jerusalem (19:32-33). Though he wishes to continue to serve the king from outside the borders of the land, he sends his servant, Chimham, along with King David, in acceptance of the king’s kindness.

But where does all of this leave us? In what way is subversive and deceitful Absalom intended to be seen as a Christ-type?

Starting back at the beginning of the Absalom story, we know that he has an evil older brother, Amnon. The two of them are sons of David, yet tension over the rape of their beautiful virgin sister, Tamar, quickly escalates. This finally leads to Amnon’s violent death at Absalom’s command. Absalom then finds himself in exile immediately following the brutal demise of Amnon.

Here is the story of not only two brothers, but of two nations of God’s people—Israel and Judah. They are related both spiritually and physically. Israel’s break from Judah following Solomon’s reign virtually signaled the beginning of false cultic worship at the direction of a non-Davidic king and his false priesthood. It is foisted upon the Father’s virgin daughter, representing God’s people. Details of the events are found in 1 Kings 12:26-33. In essence, Jeroboam rapes his sister (the Father’s daughter), taking that which is not his by demanding acts of worship to Yahweh be done outside the only God-ordained place of worship—the temple in Jerusalem. It even involves golden calves (1 Kings 12:28)! This kind of false worship is ubiquitously portrayed in terms of a sinful sexual relationship throughout the Old Testament. These actions will lead to the violent destruction of Israel (Amnon) and the eventual exile of Judah as he become lured into such improper actions, also (Absalom), and that exile will be in Babylon—a place northeast of his homeland (Geshur).

Although there will obviously be no return for Amnon, having been murdered (cp. North Israel, whose bloodline was irrevocably marred after Assyrian takeover, cp. 2 Kings 17:24ff.), eventually, Absalom will be invited back into the land by his father, David (cp. Father God welcoming Judah back to the Promised Land following Babylonian exile, cp. Isai. 49:8-13). Even after Absalom’s return, a two-year separation is maintained before the father and son are fully reunited with a kiss. Compare this with the fact that even though there was great rejoicing among the people after their return from Babylonian exile, God did not reveal himself in the same way upon the building of the new temple, leading to the weeping of the elders (Ezra 3:12). They understood the significance of God’s presence visibly falling in Leviticus 9 and 1 Kings 8—a sign which does not occur following the return from Babylon. Putting it in terms of the Absalom account, the son has now returned, but he has not been allowed into the presence of his Father (cp. 2 Sam. 14:28).

Only after a protracted time of two years and being forced to get the attention of the father-king’s right-hand man through surprisingly desperate measures (burning his field!) is the time of estrangement ended. Not only is it ended, however, but in a beautiful way, with the kiss of the father given to the formerly exiled son, signaling full restoration of the previously broken relationship. Similarly, a very long time of silence ensued following the rebuilding of the temple—about 400 years—in which God did not speak to His people through prophets. But when the silence ends, it does so in a big way. The Father actually brings the son (his people) into his very Presence (or comes to them himself, as is the case) and embraces them completely through Jesus to show the full extent of the relationship he wishes to have with them. If only this were the end of the Absalom account, our joy would be made complete, as John would say (1 John 1:4). But, alas, there is more.

Just like Absalom who, when brought into the presence of his father, was not satisfied with the station he had and the plan of his father for leading Israel (cp. 2 Samuel 15:2-6), so the majority of Israel is not satisfied with the plan of God, brought about through Jesus, for Israel’s future. Their rejection of that plan and desire to rule by force is executed through subversive and violent means intended to exact control from the rightful anointed. David’s humility is on display in the Absalom story—even letting go of his reign willingly and completely to the Father’s will and instructing those closest to him accordingly while being jeered at by his opponents (16:5-13). David’s retreat across the Kidron valley and up the Mount of Olives have already been mentioned in clear connection to Jesus’ final hours before crucifixion. Absalom continues to plot against his father, along with one who was a former close advisor to his father and who will soon take his own life by hanging (17:23). Again, we have already mentioned this event and the connection to Jesus’ betrayer, Judas, seems clear.

It is at this point in the story that a noticeable shift takes place. Early in 1 Samuel 18, the reader finds the words of the father-king stressing unequivocally his desire for his son’s safety to those who have the greatest role of authority in his kingdom, and given in the hearing of all (18:5).

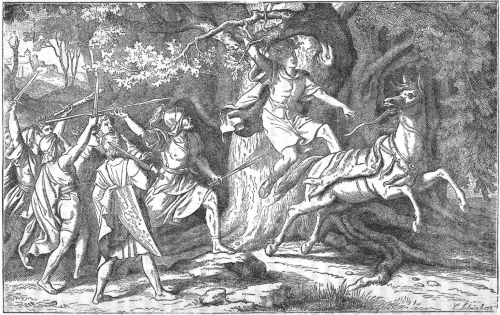

During the engagement and defeat of the rebellious son’s forces, however, which re-establishes the father-king’s rightful reign and authority, the reader is told of Absalom’s plight. After the battle, he has been caught by his long, flowing hair in the low-hanging boughs of a tree (branches around his head?; 18:9). He now hangs “suspended between heaven and earth,” as rendered by the ESV. It is a most debilitating and humiliated position for the son of the great king. At this point, the chief commander under David, knowing full well the will of the king to treat his son gently, takes it upon himself to stab (pierce) three times, with three javelins, the son on a tree, having those closest to him finish the job of execution (18:14-15).

It is here that the reader begins to discover the extent of the father-king’s love for his son. Upon hearing the news of Absalom’s death, his father, David, undergoes what can only be considered a period of disturbingly heartfelt grief (18:33; 19:1-6). Although it is a day of great victory over the king’s enemies, it comes at the great cost of a dearly loved son, causing the king to show more distress than rejoicing on what would otherwise be a day of celebration. The ruthless killer, Joab, even gets the impression that the father-king would rather have lost all his men in the battle than his dearly loved son (19:6), so great is his love.

Are we to read past the death of a loved son in a tree, pierced three times, followed by the father’s inconsolable grief without hearing a direct allusion to the Christ story? The pattern pointed out by James Jordan which is often seen in an older brother, representing the first Adam, and a younger, representing the Second Adam, certainly finds its fulfillment here again.[iv]

Upon his return following the battle, the primary emphases made in the text regard, first, his forgiveness of his most vehement opponents (19:23) and, second, his equitable judgment between a master and slave (19:29). Thirdly, he bestows honor on Barzillai, the Gileadite from the other side of the Jordan, who provides for the king and those loyal to him during their expulsion from Jerusalem (17:27-29). Even though the king wishes for Barzillai to join him in the seat of his kingdom, he is reluctant to leave his homeland late in life, but sends a younger man in his place to be the recipient of the king’s favor and to which the king readily agrees (19:38). Thus, someone who lives on the other side of the Jordan is a recipient of the king’s grace, along with those who serve under him in Israel.

We have seen grace upon former enemies, equitable judgment between those of high and low status, and a bestowal of blessing by the king upon those who live on the far side of the Jordan. Could this possibly be as clear as it seems?

In the story of this “son gone astray,” David plays two significant and fluctuating roles from a typological perspective. These roles are of, on the one hand, the true Father-King, who loves his sons (the brothers, Israel and Judah) even though their rivalry puts them at great odds with one another. As the story continues, this moves smoothly into a typology of Jesus, who, being one with the Father, is cast out of his seat of power by those who should have only the greatest respect for the Son-King. A typological transition then occurs again for David, back to the role of Father-King as he mourns almost uncontrollably the death of his greatly-loved son on a tree at the hands of those who were given clear instructions for mercy, but chose instead their own designs for ridding the Father’s kingdom of enemies. Finally, we see David once again slip into the role of a Jesus-type at the end the Absalom saga, having defeated the usurper and returning to his home with forgiveness for enemies, righteous judgment, and the bestowal of the King’s blessing on those come from the opposite side of the Jordan.

This movement between Father-type and Jesus-type is also seen in the Joseph account in Genesis as Joseph moves from most-loved son of his father (Gen. 37:3) and second in power over the known world (Gen. 41:40), to the one who, like the Father, gives the cup which causes suffering into the hands of the most-loved Benjamin, thus requiring his death while others go free (Gen. 44:2, 10, 17). Finally, Joseph moves seamlessly back into the type of Jesus when he reintroduces himself to his brothers as the one they sought to kill but the one whom the Father chose to use to save the lives of all (Gen. 45:5-7).

The typology of Absalom is no less intricate, as he starts as a type of Israel’s southern kingdom, Judah, with its “sibling rivalry” with Israel on full display. He then goes into exile, and much later returns home, yet with a substantial time of waiting before re-entering the father’s presence. Rebellious Absalom eventually becomes a type of rebellious Israel in the time of Christ, seeking to take the life of God’s anointed and making deals with those in the king’s inner circle. Finally, Absalom transitions to a type of the great King, Jesus, pierced three times on a tree by the one initially empowered to lead and protect the Father-King’s people, but who has instead become a bloody defender of legalism. It is this son for whom the Father-King mourns inconsolably and whose death marks a day of the greatest victory and yet most painful loss.

Absalom represents Israel, to be sure. From the time of the divided kingdom, Absalom’s life is a precursor of Israel’s fate. And not just in his hatred for his brother, northern Israel, and his rebellion against his Father-God, the great King, who eventually transitions into God incarnate in King Jesus. Even as Absalom-Israel forces his f/Father-k/King from his earthly throne—through the Kidron and onto the Mount of Olives—he seamlessly transitions into the Christ figure, himself, moving toward his own death pierced on a tree. Why? Because all Israel is taken up in Jesus (Isai. 53:6; Hosea 6:1-2). His death on the tree is for all of the true Israel of God (Rom. 11:26). In him are all those who rebelled and sought to take control of His kingdom as their own. He bears all of us who spurned the lordship of the Father and took what was rightfully his because of his great humility that allowed such a terrible transgression in light of even greater exoneration.

When we read of this heir-apparent turned would-be-king, we read of ourselves. Yet we also read of the only One who can free us from ourselves. The one who took on all that was in us in order to be pierced on a tree, bringing the greatest of grief to the Father in heaven and winning an unchallenged victory on a day of deepest sorrow.

Is Absalom a Christ figure? To be sure, he is.

The question that may hit home more, though: Is he an “us-figure”, too?

[i] Peter Leithart, A Son to Me: An Exposition of 1 & 2 Samuel (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2003), 260.

[ii] Leithart, 262.

[iii] Alastair Roberts makes a comparison between Joab and the snake in Eden which deserves consideration. (The Reopened Wounds of Jacob, https://theopolisinstitute.com/the-reopened-wounds-of-jacob/ [March, 2019])

[iv] Through New Eyes (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers: 1999), 188.